Social Media’ Impact on Digital Discourse and Engagement

By Devin Vucic 5/12/25

Introduction

Adolescents today are growing up in a world where social media and digital technologies are progressively establishing the bounds of political participation. Social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and X (formerly Twitter) are places where individuals develop and alter their identities. These platforms can increase political awareness for adolescents while creating a polarizing environment (Baumgartner & Morris, 2006). While these platforms provide opportunities for youth to become more politically active, they also introduce challenges – such as ideological polarization and misinformation. These dynamics can vary between countries but are most prominent in the United States and occur during particular presidential administrations. The administrative actions made by the government can lead to a spike in misinformation and can affect the pool of future voters, specifically evident during the Trump administration (Penney, 2019).

Political socialization and its theories form the foundation of understanding how adolescents acquire political attitudes and develop civic identities. While traditional influences like family and education remain significant, digital environments/media have disrupted these processes. Political identity has become increasingly fragmented, mediated not by central authorities but by decentralized, algorithmically curated feeds. Fisher (2008, 2012) notes how youth today often mix electoral and activist strategies influenced by pragmatic concerns and idealistic visions. In such a hybrid landscape, digital engagement can serve as an entry and end point for civic expression.

Expanding on this dynamic, the theme of “hybrid activism,” particularly among marginalized individuals, as discovered by Lee (2022), highlights how these individuals use anonymity and reach on social media to participate in covert forms of online activism. This speaks to a more significant cultural shift that social media is not merely a distribution mechanism for political speech but also a political space itself. Today’s adolescents curate and produce significant political content rather than being passive consumers. The necessity of examining young people’s online interactions with political content and how these interactions result in offline activism and protest is emphasized by this framework. Corroborating the importance of studying these online behaviors, they can also be explored further in terms of subspecific race, gender, and even socio-political profiles. The perspective that Velázquez (2023) explores shows how socio-political indicators influence Latinx youth to experience systemic barriers and institutional distrust. Although centered on child welfare, this study reveals patterns of civic disillusionment among marginalized communities, emphasizing the need to consider how intersecting factors, like ethnicity, influence political participation. Similarly, political issues also take the spotlight in determining politically based social media dialogue – the recent climate crisis being one major topic (Khan & Nuermberger, 2022).

Moreover, the influence of political figures plays a pivotal role in shaping adolescent political efficacy. Discussions around this topic include points that younger individuals (under 18) calibrate their political behaviors based on perceived authenticity and trust in their government’s leadership, which is often now filtered through the lens of social media (Dunn et al., 2022).

Literature Review

Social Media as a Catalyst for Youth Political Engagement

The transformative role of social media in redefining political engagement, specifically for the youth of the United States, is profound and multifaceted. Through platforms like X, Facebook, and TikTok, political humor and satire, as explored by Baumgartner and Morris (2006), have become instrumental in engaging young audiences while simultaneously inducing skepticism towards traditional political and media vessels. This dual role of social media helps foster a politically aware yet critical electorate – where humor entertains and provokes deep thought and questioning of political realities. Similarly, the illustration of a significant shift in youth behavior on social media during the Trump administration (2016-2021) is continuously noted to be behind battles on social platforms for countering misinformation and extremist narratives (Penney, 2019). Young individuals consume political content and actively create and disseminate it, utilizing the viral nature of digital platforms to influence a growing political discourse. This is a concept noted as “hybrid activism,” – which further exemplifies how the group of marginalized youth, in particular, harnesses social media’s potential for anonymity and extensive reach to engage in covert activism—navigating around an increasing threat of surveillance and censorship online (Lee, 2022). This kind of activism showcases the adaptability of adolescents who exploit digital platforms for political expression while protecting their identities. Moreover, the influence of political figures indicates that engagement is intricately linked to their perceptions of political parties and their leaders (Dunn et al., 2022). This highlights how different political climates and leadership styles can catalyze or discourage political participation across the globe, with social media serving as a primary area for these types of interactions.

Collectively, these studies showcase the dynamic and interactive landscape where young individuals are not passive consumers of information in local politics but active participants in shaping narratives. With its dual capacity to engage and educate, social media is a critical tool in adolescents’ global mobilization and empowerment.

Evolution of Youth Political Identity

The evolution of youth political identity over recent decades highlights a significant shift from traditional forms of civic engagement towards a more dynamic and personalized style of expression. Braungart suggests that political orientations among young people often reflect generational shifts influenced by historical, social, and familial contexts (1990). This foundation is fundamental for understanding the continuity and evolution of political behaviors across generations, where the interplay between inherited political norms and personal beliefs shapes political identities for adolescents. The integration of activism and electoral politics among the youth further illustrates this shift – showing how younger generations are increasingly likely to engage in politics through traditional and non-traditional means, driven by a blend of idealism and pragmatism (Fisher, 2008 & 2012). This trend is particularly evident in how digital platforms have enabled new forms of civic engagement. They facilitate a seamless integration of social movements and electoral strategies, where political leaders, future candidates, and the electorate unite to win elections and potentially drive hysteria.

Additionally, exploring the effects of political partisanship and polarization regarding youth engagement reveals that heightened political climates can spur greater political participation among teenagers (Khosla, 2022). Rather than deterring engagement, intense political environments may clarify the stakes involved – thus motivating young individuals to participate more actively in complex political processes. These depictions put a spotlight on a complex landscape where youth political identity is continually being shaped by both their immediate social and political environments and also by a broader cultural and technological change that heightens and changes every four years in the United States (Braungart, 1990; Fisher, 2008 & 2012; Khosla, 2022; Penney, 2019). Understanding youth political identity years ago requires a nuanced approach considering past political movements’ historical legacies and digital culture’s transformative impacts.

Sociopolitical Context and its Influence on Youth Activism

The broader socio-political context significantly influences youth activism, linking historical movements to contemporary strategies and challenges. Historical analysis of the NAACP Youth Council provides an interesting perspective on how early civil rights activism laid the groundwork for modern movements – demonstrating the enduring impact of structured youth involvement in socio-political struggles (Hale, 2016). This historical backdrop is essential for acknowledging how past strategies inform current youth activism. In a contemporary setting, political leaders significantly impact adolescents’ political ideas (Dunn et al., 2022). The research underscores the reactive nature of youth activism towards their political figureheads, where young individuals are either becoming more active or engaged based on their perceptions and experiences with current leadership. This dynamic interplay highlights how political figures can act as catalysts or barriers to activism amongst younger individuals – where their actions can determine their next elections. Additionally, the importance of innovative research methodologies to capture the many diverse forms of political participation among adolescents is ever-growing – calling for a comprehensive approach to studying how young people interact with one another online and with political content they might come across on social platforms (Weiss, 2020; Lee, 2022). The synthesis of historical, contemporary, and methodological insights offers a framework for understanding the socio-political development of youth activism, emphasizing the need for adaptive strategies that respond to enduring legacies and emerging challenges in the political engagement of young individuals.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of two sets of individuals: (1) a large variety of Freshman-Seniors from X High School (14-19-year-olds) and (2) a smaller variety of 5 hand-picked students also from X High School who were barred from participating with the first group of participants.

Design Type

This design incorporates a somewhat “sequential” exploratory strategy utilizing quantitative and qualitative methods. An individual’s exposure to social media and other media sources was the independent variable, and political participation was the dependent variable in this study.

In 2017, Pontes and two other researchers conducted a study that analyzed patterns among adolescents in Britain and their opinions/engagement in local politics, specifically those without a General Certificate of Secondary Education in Computer Science (GCSE-CS). Through a series of questionnaires, they found that students who hold a GCSE-CS are more informed about their local political parties and are more willing to participate in civic ordeals and that non-GCSE-CS students are more likely to vote based on party leadership rather than policy (Pontes et al., 2017).

Alongside the survey, in 2019, Penney conducted an experimental study that revealed certain behaviors in a group of individuals in the Northeast of the United States. A focus group session showed that during the Trump administration in the United States, participants felt they had to combat far-right ideologies, counter misinformation, and utilize social media for personal and political self-exploration (Penney, 2019).

Data Collection Tools

A survey comprising six sections containing five questions was distributed among the student body through individual classrooms and a school-wide digital announcement. The announcements and sharing of the survey were distributed via Schoology, a learning management system utilized by faculty at X High School.

A group of 5 hand-picked students from X High School were asked to participate in a focus group session to find commonalities and nuances from the survey results (Penney, 2019). The group convened in a closed, comfortable environment to reduce stressors that could have produced unprovoked ‘variety’ in their responses. They were also barred from partaking in the survey to reduce the potential knowledge of questions that would be asked.

Procedure

The survey was announced through X High School’s digital communication platform(s) to inform participants about the initiation of the study. It was distributed electronically to all students (those of the 2024-2025 school year) aged 14-19 at X High School via Google Forms. Google Forms is a survey system software a part of the more extensive web-based Google Docs suite offered by Google. Students were given a set timeframe of 5 months to complete the survey, with reminders being published via Schoology one day before the response window was closed.

Without regard to the survey respondents, five students were selected based on their diverse political views and social media usage to participate in a focus group held in a closed conference room at X’s public library. These participants were predetermined prior to the launch of the questionnaire and were barred from participating in the survey. The researcher moderated this session and guided the discussion using five predetermined questions that would align with the research question. Four follow-up questions were asked to multiple random participants at different times throughout the session. This session lasted approximately 45 minutes and was audio recorded using Apple’s Voice Memos. Voice Memos is a popular portable audio recorder that can record and transcribe audio pieces.

Reliability and Validity

This study has implemented several measures to ensure the reliability and validity of the findings. For reliability, the survey questions have been standardized and structured to be unambiguous – this choice was made to reduce the variability in responses due to interpretation. Additionally, the survey tool, Google Forms (see Procedure), ensures consistency in how each participant accesses and completes the questions. Thus supporting reliable data collection across a relatively large sample. The focus group addressed reliability by following a standardized protocol of questions and prompts and ensuring that each participant encountered the same core topics and questions.

Validity is strengthened through the ‘sequential’ exploratory design approach. This allowed the initial survey results to inform and refine the focus group questions to allow for deeper insights into the nuances of the survey. This strategy also minimizes the risk of irrelevant and/or extraneous variables and ensures that the study focuses on the relationship between media exposure and political engagement. The choice of a mixed method also enhances construct validity as quantitative and qualitative data provide evidence that converges for the study’s conclusions. Furthermore, the data analysis methods were designed to maintain internal validity – with quantitative correlations from the survey and thematic (qualitative) analysis from the focus group offered complementary insights into adolescents’ engagement patterns with social media.

Ethical Considerations

This study adheres to ethical standards in all aspects of its design and execution. Prior to the data collection period, implied (Appendix A), informed (Appendix B), and assent forms (Appendix C) were obtained from all participants. These forms varied based on the type of participant and which portion of the study they would be participating in. There was a strong emphasis on explaining the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and potential benefits. For participants under 18, parental consent was obtained in compliance with ethical guidelines for research involving minors. All participants were assured anonymity – survey and focus group data were kept confidential, with no personal identifiers captured. However, if personal information was collected in the transcript of the focus group, those identifiers were redacted. Students were also not referenced by name in the focus group and were instead referenced as Students 1-5. This choice was made for privacy and to reduce potential bias from the researcher’s post-data collection. For survey respondents, identifiable information was not collected, and responses were coded to protect individual, anonymous identities.

In the focus group, participants were reminded of their right to withdraw without penalty. The group convened at X’s public library in a safe, relaxed conference room to reduce stressors and maintain calm throughout the conversation. Participants and guardians were also given two forms before the focus group. Minors were provided with assent forms, while parents/guardians were provided informed consent forms that required the researcher to explain the study thoroughly and required signatures from both the minor/parent and the researcher.

Data Analysis Plan

The analysis for this study followed a two-phase approach, aligning with the mixed-method design. The first phase consisted of a quantitative analysis of survey data (1), while the second phase focused on a thematic analysis of qualitative data pulled from the focus group (2). This dual approach allowed a comprehensive understanding of the media’s influence on adolescents’ political engagement.

In the quantitative phase (1), survey data was analyzed using statistical software, Google Forms, and Google Sheets to identify patterns and correlations between media exposure (the independent variable) and levels of political engagement (the dependent variable). Descriptive statistics provided an overview of general trends in media use among the participants. Additionally, inferential statistics (i.e., correlation coefficients and regression analysis) were applied to examine the relationship between the frequency and type of media exposure and participants’ political engagement.

The qualitative phase (2) analyzed focus group data through thematic analysis. The focus group was recorded and reviewed to identify recurring themes and unique perspectives regarding how the participants viewed social media’s relationship with their own political engagement (Penney, 2019). Central themes were highlighted and corroborated with one another, along with the data pulled from the survey, to deduce commonalities.

Limitations

This study, while comprehensive in its approach, was subject to several limitations that may have affected the findings. The generalizability of the results may have been constrained by the sample, which consists only of X High School students. As a result, the findings may not fully capture the attitudes and behaviors of adolescents from different socio-political and cultural contexts.

Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases, like desirability. This could be where participants respond in ways they perceive as socially acceptable rather than providing their genuine opinions. This study’s cross-sectional design also limits the ability to establish causal relationships between media exposure and political engagement.

Regarding the focus group component, while diverse, the small sample of five participants may not capture all perspectives within the larger adolescent population. This limitation could result in over-representing certain viewpoints that may not reflect broader trends.

While these limitations exist, they are addressed further in the Discussion section, which explores their potential impacts on the study’s findings and suggests avenues for future research.

Results

The intersection of the questionnaire and focus group data offers a multifaceted portrait of adolescent political engagement at X High School during a recent “digital boom” in politics. While the questionnaire (Outcome 1) provides an approximate overarching view of student attitudes toward political content online, the focus group (Outcome 2) adds depth and nuance. Participants in the focus group often expressed conflicted attitudes about their digital political experiences–highlighting how engagement does not always equate to belief or action. These perspectives, outlined in recurring themes within the focus group, build upon the various striking results seen in the data pulled from the questionnaire.

Outcome 1 – Questionnaire

From the 141 questionnaire results, adolescents at X High School engage with social media extensively, with a majority (approximately 60%) reporting usage between two and four hours daily. Respondents were also asked how they obtained their information about politics – general news media sources (e.g., CBS, ABC, NBC) were used as a control to determine if students rely on traditional media sources instead of social media. This answer choice received 48 student responses (34%).

As discussed prior, an overwhelming 91.5% of respondents at X High School use social media for more than 1 hour a day, and X/Twitter (16.3%), TikTok (43.3%), YouTube (47.5%), and Instagram (48.2%) were among the most used social media sites to obtain political information. Despite the high exposure to social media outlets, the amount of time each student uses social media to actively and solely gather political information varies. 117 (82.9%) of student respondents claimed they spend none or 15-30 minutes daily consuming political content.

Political Trust and Information Verification

One of the key findings from this study is the level of skepticism among the student body regarding the credibility of political information on social media. A majority of students, 86 (61%), responded “maybe” to a question asking if they trusted political information they found while scrolling on social media. In the same question, only 15 (10.6%) students expressed confidence in the accuracy of the information they found, responding “yes.”

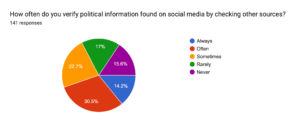

Figure 1: Student responses concerning verification habits about political information found on social media.

Verification habits varied significantly among participants. Students were asked how often they verify political information on social media sites with various answer choices, including always, often, sometimes, rarely, or never (see Figure 1 above). On the most polar of the answer choices, 20 students (14.2%) responded “always” to verifying information consumed – whereas 22 students (15.6%) responded “never” to information verification. More centric answer choices received the most amount of student answers, as follows: “often” was chosen by 43 students (30.5%); “sometimes” was chosen by 32 students (22.7%); and “rarely” was chosen by 24 students (17%). A correlation analysis revealed that individuals who responded that they did not trust political content on social media were likelier to verify that information. In contrast, those who trust political findings tend to do so less frequently, suggesting skepticism may drive critical engagement with political content.

Engagement with Political Figures and Movements

At the beginning of the questionnaire, students were asked about their active engagement with politically related posts/forums online, including whether they followed political figures, parties, or activist groups. The responses were relatively split evenly, with 77 students responding “no” (54.6%) and 64 students responding “yes” (45.4%) to the question of whether they follow political figures and/or parties.

The questionnaire had an entire section of 5 questions dedicated to domestic political engagement. The answers stayed consistent throughout each question, as seen in Figure 2 below, which shows the questions in this section of the questionnaire and the similarities within the responses.

Figure 2: Question/Responses for Section 3 of the Questionnaire

Question | Answer Options | Student Responses |

Have you ever shared political content on social media? | Yes; No | 39 (27.7%), Yes; 102 (72.3%), No |

Have you ever participated in a political event (e.g., protests, campaigns, rallies) because of what you saw on social media? | Yes; No | 18 (12.8%), Yes; 123 (87.2%), No |

Does exposure to political content on social media make you more likely to engage in discussion about politics? | Yes; Maybe; No | 72 (51.1%), Yes; 29 (20.6%), Maybe; 40 (28.4%), No |

Have you ever posted or created ORIGINAL political content (e.g., videos, articles) on social media? | Yes; No | 11 (7.8%), Yes; 130 (92.2%), No |

Has political content on social media ever caused you to change your voting intentions? | Yes; Maybe; No | 13 (9.2%), Yes; 17 (12.1%), Maybe; 111 (78.7%), No |

Impact of Social Media on Political Participation

One of the most compelling findings in this study is the relationship between social media activism and offline political engagement. When asked if exposure to political content on social media inspired the individual to engage in dialogue related to politics, 72 students responded “yes” (51.1%), 29 students responded “maybe” (20.6%), and 40 students responded “no” (28.4%). However, the same can not be said about engaging with local representatives or elected officials because of social media exposure – where an overwhelming majority of 123 students (87.2%) said they have never contacted an elected official because of what was happening or trending on social media despite numerous social media “meltdowns” in recent years.

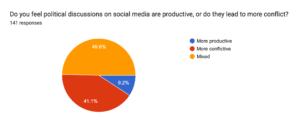

Figure 3: Chart showing student responses on opinions about social media discussions.

Similarly, when asked if they feel that political discussions are either productive or lead to more conflict, only 13 students (9.2%) answered that they felt these discussions were “more productive.” On the other hand, a near majority of students, 70 (49.6%), answered that these discussions are “mixed.” The remaining 58 (41.1%) answered that they felt as if these social media discussions were “more conflictive.”

Outcome 2 – Focus Group

The focus group discussions provided more profound insights into how social media shapes political awareness, engagement, and polarization among adolescents at X High School. The questions highlighted three major themes and nuances discovered during this study’s questionnaire phase. These questions were intentionally designed to spark open-ended responses compared to one-word answers, helping deep-dive into some of the key questions predetermined to the launch of the questionnaire and focus group launch.

Figure 4: Unique Questions Asked to Focus Group Participants

Question |

How do you usually get your news information about political events or issues? Do you find yourself relying more on social media, traditional/legacy news outlets, or a combination of both? |

Can you think of a time when something you saw or read on social media influenced your opinions on a political issue? |

Do you feel that what you read on social media motivates you to take political action (e.g., attending protests, signing petitions, or sharing information)? |

When discussing political topics online, do you feel your peers are more open to debate and conversation, or do you notice polarization? How does that environment impact your willingness to engage? |

In your opinion, does social media make it easier or harder to understand political issues? Are there any platforms or influencers you follow to help explain political topics clearly? |

Recurring Theme 1: Social Media as an Entry Point for Political Awareness

The focus group reaffirmed that social media is the primary source of political information for most students, echoing the survey’s findings that 91.5% of respondents use social media for more than one hour daily. Participants also emphasized Instagram and TikTok as social media mediums that each of the 5 participants used most – aligning with the responses the student body answered in the questionnaire (Instagram receiving 48.2% and TikTok receiving 43.3% of the questionnaire response). However, students 3 and 5 acknowledged that their engagement with political content is often passive – a trend also seen within the questionnaire.

Recurring Theme 2: Skepticism of Information

Another key theme was the uncertainty surrounding the credibility of political information on social media. Students 2 and 5 said on multiple occasions (during different questions) that they would only fact-check information that they assumed to be “extreme” or “exaggerated.” On the other hand, student 4 argued that they fact-check even the mildly extreme pieces of information. This skepticism, seen by ⅘ of the focus group, mirrors the questionnaire results – where 61% of students responded “maybe” when asked if they trust political information, and only 10.6% responded “yes” (see Figure 1).

Recurring Theme 3: Political Discussion – Awareness vs. Action

Despite the high political content exposure on social media, the focus group revealed a disconnect between awareness and action. Several participants noted that while they engage in political discussions online or among peers, they are less likely to take real-world action based on the content on social media. This aligns with the survey findings that show that while 51.1% of students said political content makes them more likely to engage in discussions – actual activism rates remain low:

- Only 12.8% of students had attended a political event (e.g., protests, rallies, campaigns) because of social media.

- Only 7.8% had created original political content.

- Only 9.2% reported changing their voting intentions due to social media exposure.

The focus group also emphasized that political discussions on social media often lead to conflict rather than productive conversations. Students 1, 3, and 4 agreed that the productiveness of conversation heavily relied on who the other converser was and the emotional setting. The three students argued that ignorance and political efficacy, among other traits, were determining factors of how productive a conversation would be regarding recent political events – especially on issues like the conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine. The overall tone of the larger body of the focus group came to a consensus at the end of the question that these conversations were more conflictive in their entirety, reinforcing the questionnaire’s finding that 41.1% of students felt online political discussions were more conflict-driven than constructive.

Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the complex and evolving role of social media in shaping political engagement among adolescents at X High School. The data suggests that while social media platforms serve as primary sources of political information, there remains a significant gap between exposure to political content and actual political participation. These findings align with existing literature on digital political engagement, reinforcing that social media facilitates awareness but does not necessarily translate into meaningful action (Baumgartner & Morris, 2006; Penny, 2019; Fisher, 2012).

One of the most significant findings of this study is the overwhelming prevalence of social media usage among adolescents – with 91.5% of respondents using these platforms for more than an hour daily. Instagram and TikTok, despite the app’s recent controversy, emerged as the dominant sources of political information – supporting the assertion that young adults prefer visually engaging and algorithm-based content (Baumgartner & Morris, 2006). However, despite the high exposure level, most respondents (82.9%) reported spending minimal time actively consuming political content. This suggests that some may either stumble upon and engage with this information and that this content remains secondary to entertainment-focused social media usage. This echoes prior research indicating that political humor and satire serve as entry points for political awareness rather than active participation (Baumgartner & Morris, 2006; Fisher, 2012).

The study also reveals a deep skepticism among students regarding the credibility of political information on social media. A majority (61%) expressed uncertainty about the trustworthiness of the political content they encountered, and only 10.6% affirmed confidence in its accuracy. This skepticism was further supported by students’ self-reported verification habits – which varied significantly: while 14.2% always claimed to fact-check information, 15.6% admitted to never doing so. The focus group findings reinforce this trend, with several participants stating they primarily verify information that appears to be “extreme” or “exaggerated.” These results suggest that while exposure to misinformation is a concern, students exhibit a level of media literacy by questioning the validity of online political content. However, as Penny (2019) and Dunn et al. (2022) note, many adolescents lack the tools to counteract misinformation, potentially reinforcing ideological echo chambers effectively.

Another key insight from the study is the division in students’ engagement with political figures and movements. While 45.4% reported following political figures and/or activist groups on social media, participation in political discourse and activism remained low. Only 27.7% of respondents reported sharing political content, and an even smaller percentage (12.8%) had attended a political event due to social media exposure. The focus group discussions supported these findings, with participants emphasizing that while they engage in discussions online, they rarely take concrete actions. This suggests that social media activism among adolescents is often performative – which aligns with broader discussions about “clicktivism,” where engagement remains superficial rather than leading to substantive political participation (Penney, 2019; Khosla, 2022; Lee, 2022).

Moreover, the study highlights the perception that social media-fueled political discussions tend to be more conflict-driven rather than productive. 41.1% of student respondents viewed these discussions as more divisive than constructive – a sentiment echoed in the focus group. Participants noted that online discourse’s perceived hostility and polarization deterred them from engaging further in political conversations. This finding aligns with broader concerns about digital political polarization, where algorithmic content curation amplifies divisive narratives and discourages meaningful debate and engagement (Baumgartner & Morris, 2006; Braungart & Braungart, 1990; Khosla, 2022).

Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. One primary limitation is the sample population, which was restricted to X High School students. This geographical constraint limits the generalizability of the findings to adolescents in different sociopolitical contexts. Political engagement levels and media consumption habits may differ significantly based on regional, cultural, and socioeconomic factors. Future studies should expand the participant pool to include a more diverse cross-section of adolescents across various cities, counties, or states to obtain a broader understanding of these important dynamics.

Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the potential for response bias. Participants may have over- or under-reported their social media usage, political engagement behavior, or skepticism toward information sources due to social desirability bias or recall inaccuracies (these data examples were collected in this study’s qualitative and quantitative portions). While efforts were made to frame questions neutrally, this inherent limitation in self-reported data collection remains a concern.

Another limitation is the small sample size of the focus group portion of this study’s methodology. Although the five participants were selected to represent diverse viewpoints, their experiences may not fully encapsulate the broader range of adolescent political behaviors. A larger sample or multiple focus group sessions through data collection may yield a more representative and nuanced understanding of how adolescents interact with political content on social media.

Furthermore, this study primarily examines correlation rather than causation. While the data suggests strong links between social media exposure, skepticism toward political content, and political engagement levels – it does not establish a direct causal relationship. A longitudinal study tracking participants over time would provide deeper insights into how prolonged exposure to politics influences their engagement and beliefs. A similar challenge involves the rapidly evolving nature of social media platforms. Since political discourse on social media is heavily influenced by algorithmic changes, trending topics, and evolving platform policies, this study’s findings may become outdated as the digital landscape shifts. Future studies could incorporate portions of their methodology to discover how algorithms work in real time and participants’ reactions to different media types across different platforms. Alongside this, future research should consider repeated studies across different election cycles or significant political events to assess how trends in youth engagement fluctuate over time.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that while social media plays a significant role in shaping adolescents’ political awareness, the impact on actual participation remains limited. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok expose students to political content and drive skepticism toward misinformation, all while contributing to the perception that online discussions are conflict-driven and often hamper deeper engagement. The distinction between digital activism and real-world political action further highlights the challenges of fostering meaningful civic engagement through social media.

The study’s results reinforce concerns about the performative nature of online political engagement, with many students engaging in discussions but few taking action. Given the evolving nature of the digital landscape, future research should investigate how algorithmic changes influence adolescents’ exposure to political content and its long-term effects on their political efficacy. Expanding the study across diverse socio-political contexts could further refine these findings and contribute to broader discussions on the role of social media in youth political socialization.

References

Baker, C. N. (2023). History and politics of medication abortion in the United States and the rise of telemedicine and self-managed abortion. Journal of Health Politics, Policy & Law, 48(4), 485-510.

Baumgartner, J., & Morris, J. S. (2006). The daily show effect. American Politics Research, 34(3), 341-367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673×05280074

Braungart, M. M., & Braungart, R. G. (1990). Studying youth politics: A reply to flacks. Political Psychology, 11(2), 293. https://doi.org/10.2307/3791691

Dunn, D., Wray‐Lake, L., & Plummer, J. A. (2022). Youth are watching: Adolescents’ sociopolitical development in the trump era. Child Development, 93(4), 1044-1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13762

Fisher, D. R. (2012). Youth political participation: Bridging activism and electoral politics. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 119-137. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23254589

Fisher, P. (2008). Is there an emerging age gap in US politics? Society, 45(6), 504-511.

Hale, J. (2016). The politics of youth: Personal conceptions of adolescence, the NAACP Youth Councils, and student activism in the south, 1900-1965. AERA Online Paper Repository.

Khan, N., & Nuermberger, C. (2022). The problem with children in politics: The documentary evidence of youth climate activism. Anthropology in Action, 29(3), 31-39.

Khosla, V. (2022). Political partisanship, extreme polarization and youth voter turnout in 2020. Penn Journal of Philosophy, 17(1). https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/47169

Lee, A. (2022). Hybrid activism under the radar: Surveillance and resistance among marginalized youth activists in the united states and canada. New Media & Society, 26(7), 3833-3853. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221105847

Penney, J. (2019). ‘It’s my duty to be like “this is wrong”‘: Youth political social media practices in the trump era. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 24(6), 319-334. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmz017

Pontes, A. I., Henn, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Youth political (dis)engagement and the need for citizenship education: Encouraging young people’s civic and political participation through the curriculum. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 14(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197917734542

Velázquez, J. A. (2023). Sociopolitical indicators that may influence latinx children’s and youth’s entry into the child welfare system and services. Child Welfare, 100(4), 1-20.

Weiss, J. (2020). What is youth political participation? Literature review on youth political participation and political attitudes. Frontiers in Political Science, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2020.00001

Yaakub, M. T., Mohd Kamil, N. L., & Wan Mohamad Nordin, W. N. A. (2023). Youth and political participation: What factors influence them? Jurnal Institutions and Economies, 15(2), 87-114. Abstract from Youth and Political Participation: What Factors Influence Them?, 2023, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.22452/ijie.vol15no2.4

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.